Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Appreciation

This course is from Interaction's ready2work range and is developed and maintained in collaboration with the First Nations team at Krueger Consultancy Services. You can click here for an overview of the course navigation options or scroll down if you are ready to get started.

Respect

Interaction recognises and respects Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Nations people in Australia. ‘First Nations peoples’ is used to reference the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. We will no longer use the word ‘Indigenous’ in relation to the First Nations peoples, communities, and businesses of Australia.

First Nations people should know that this course contains images, voices and names of deceased persons. In some communities, hearing recordings, seeing images, or the names of deceased persons may cause sadness or distress.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we live and work.

We would also like to pay respect to the Traditional Owners of this land, acknowledge Elders both past and present, and extend that respect to the other First Nations peoples who may be participating in this course.

Prelude Waterhole

In this course, we will explore a series of waterholes, each of which will enhance your understanding and deep appreciation for the world's oldest continuous living culture.

Australia’s First Nations peoples are two distinct cultural groups, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. There is great diversity within these two broadly described groups, exemplified by the over 250 different language groups spread across the nation.

Aboriginal Peoples

Aboriginal peoples are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent, and their descendants share biological ancestry back to the original occupants of mainland Australia. This includes Tasmania, K’gari, Palm Island, Mornington Island, Groote Eylandt, Bathurst, and Melville Islands.

It is estimated that 300,000 to 950,000 First Nations people lived in semi-nomadic family groups that followed seasonal changes within a defined area. Each family group belonged to certain territories and had spiritual connections and obligations to that country.

Membership within each family group is established through birthright, shared language, and adherence to cultural obligations and responsibilities.

This framework prioritises social and spiritual engagements over material possessions, placing emphasis on the profound connection between individuals and their ancestral customs.

The concept of land ownership is distinct.

Rather than perceiving land as something to be owned, Aboriginal people view themselves as belonging to the land. They perceive it as a profoundly symbolic and spiritual landscape, far beyond its physical characteristics. The land is a source of cultural significance and spiritual nourishment for Aboriginal communities.

Torres Strait Islander Peoples

There are approximately 270 islands in the Torres Strait Island region, remnants of the Sahul Shelf. This now-submerged land bridge linked the Australian mainland and Papua New Guinea.

Torres Strait Islanders live permanently in 20 communities on 17 of the Islands and in locations in every Australian state. Two communities, Seisia and Bamaga, sit on the Queensland coast as part of the Northern Peninsula Area (NPA).

Torres Strait Islanders are not mainland Aboriginal people who inhabit the Torres Strait.

Torres Strait Islander culture has a unique identity and associated territorial claim. The Arrernte people (pronounced Arrenda and known in English as the Aranda) are the original custodians of Arrernte lands in the central area of Australia around Mparntwe (Alice Springs) in the Northern Territory, where they have lived there for more than 20,000 years.

Respecting Identity

Many Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islander people find the term Indigenous to be overly generic and disrespectful. Other terms and acronyms that should not be used to describe First Nations Peoples include ATSI, Natives, and Coloured. Preferred terms that are both generic and acknowledge the diversity of Australia’s First Peoples include:

- First Nations Australians

- First Nations peoples

- and Sovereign peoples.

Each person has their specific clans, groups, communities, islands, and nations that they identify with and which are relevant to the greater region they are connected to. Aboriginal people have referred to themselves, for example, as:

- Murri – Queensland and Northern Territory

- Koori – New South Wales and Victoria

- Nunga – South Australia

- Noonga – Western Australia

First Nations identities can also directly link to their language groups and traditional country (a specific geographic location); for example, Gunditjamara people are the traditional custodians of western Victoria, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation are from Sydney, and the Yawuru people are the traditional custodians of Broome in Western Australia.

Torres Strait Islander people prefer to use the name of their home Island to identify themselves to outsiders; for example, a Saibai man or woman is from Saibai, or a Meriam person is from Mer. Many Torres Strait Islanders born and raised in mainland Australia still identify according to their Island homes.

Ways of Identifying are Personal and Individual

Find out the preferred term from the respective Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander group or individual you refer to. Ask people what they prefer while recognising that their preference may not be the case for others.

Remember, hundreds of diverse groups and languages exist throughout the nation, not just one mob.

Population

The Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021 Census recorded these key statistics:

-

984,000 First Nations people living in Australia, representing 3.8% of the total Australian population.

-

This was an increase of 185,600 people (23.2%) since 30 June 2016

-

One-third (33.1%) of the First Nations population was under 15 years of age

The Census found that First Nations population had a younger age structure than the rest of the Australian population. Larger proportions of young people and smaller proportions of older people reflect higher birth rates and lower life expectancy in First Nations peoples.

Identity

Despite the similarities in culture and history, there are many different First Nations groups in Australia. First Nations peoples identify themselves with names from the specific region in Australia they have inhabited.

-

Click here to display an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Language Map, then locate the suburb you live in on the map and find the name of the language group you are in today.

Aboriginality is Defined by Relationships - Not Skin Colour

First Nations refer to their nation when identifying themselves: 'I am a Dharawal man' or 'I'm an Eora woman'.

Today, a First Nations person is defined as a person who:

- is of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent

- identifies as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

- is accepted as such by the community in which he (she) lives

Urbanisation

First Nations people, like all cultures, are evolving contemporary cultural forms and practices. 75 per cent of First Nations people now live in urban and regional environments, which does not mean they are removed from their culture. The people maintain strong links to 'traditional' culture, including ongoing contact with country (traditional land), family and communities.

First Nations Music

Music is a powerful element of First Nations culture and is part of everyday life as well as a vital part of sacred ceremonies. Traditional music is still performed widely and there is also a very strong and lively contemporary music scene.

Music plays a major role in traditional Aboriginal societies and is intimately linked with a person's ancestry and country (the animals, plants and physical features of the landscape). It is traditionally connected with important events such as the bringing of rain, healing, wounding enemies, and winning battles.

Contemporary First Nations music continues to merge earlier traditional sounds with contemporary mainstream music styles.

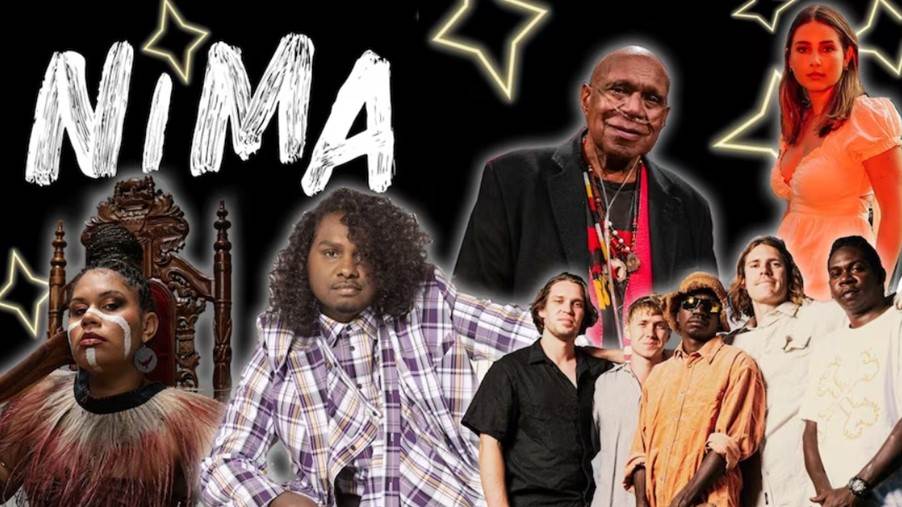

Promoting First Nations achievement as a marketable and growing force within wider Australia, NIMA provides a wonderful forum for the wider community to learn about First Nations music.

PLEASE NOTE: THE FOLLOWING PAGES INCLUDE IMAGES OF DECEASED PERSONS

Jessica Mauboy

Jessica Hilda Mauboy was born and raised in Darwin, Northern Territory, she is a descendant of the KuKu Yalanji nation of Far North Queensland. Mauboy rose to fame in 2006 on the fourth season of Australian Idol, where she was runner-up and subsequently signed a recording contract with Sony Music Australia. Mauboy is one of Australia's most successful female artists. She has achieved six top-ten albums (including two number-ones) and 16 top-twenty singles (including 9 top-ten hits). She has won two ARIA Music Awards from 25 nominations and was ranked sixteenth on the Herald Sun's list of the "100 Greatest Australian Singers of All Time".

Click here for more biography / visit Jessica’s official website.

Christine Anu

Christine Anu is one of Torres Strait Islander’s most successful performers and one of Australia's most popular recording artists. Anu is a renowned singer, songwriter, and actress. With her vibrant voice and versatile performances, she gained fame in 1993 with her debut album "Stylin' Up," featuring hits like "My Island Home" and "Party." Anu's career has encompassed successful theatre and television roles. Beyond her artistic achievements, she advocates for indigenous rights and environmental sustainability. A cultural ambassador and inspiration to artists worldwide, Christine Anu's impact on Australian music and the arts is profound.

Click here for more biography / visit Christine's official website

Baker Boy

Danzal James Baker OAM, known professionally as Baker Boy, is a Yolngu rapper, dancer, artist, and actor. Baker Boy is known for performing original hip-hop songs incorporating both English and Yolŋu Matha and is one of the most prominent Aboriginal Australian rappers. He was made Young Australian of the Year in 2019, and his song "Cool as Hell" was nominated in several categories in the 2019 ARIA Awards. In 2018, he won two awards at the National Indigenous Music Awards and was named Male Artist of the Year at the National Dreamtime Awards. His debut album, Gela, was released on 15 October 2021. At the 2022 ARIA Music Awards he won five categories from seven nominations.

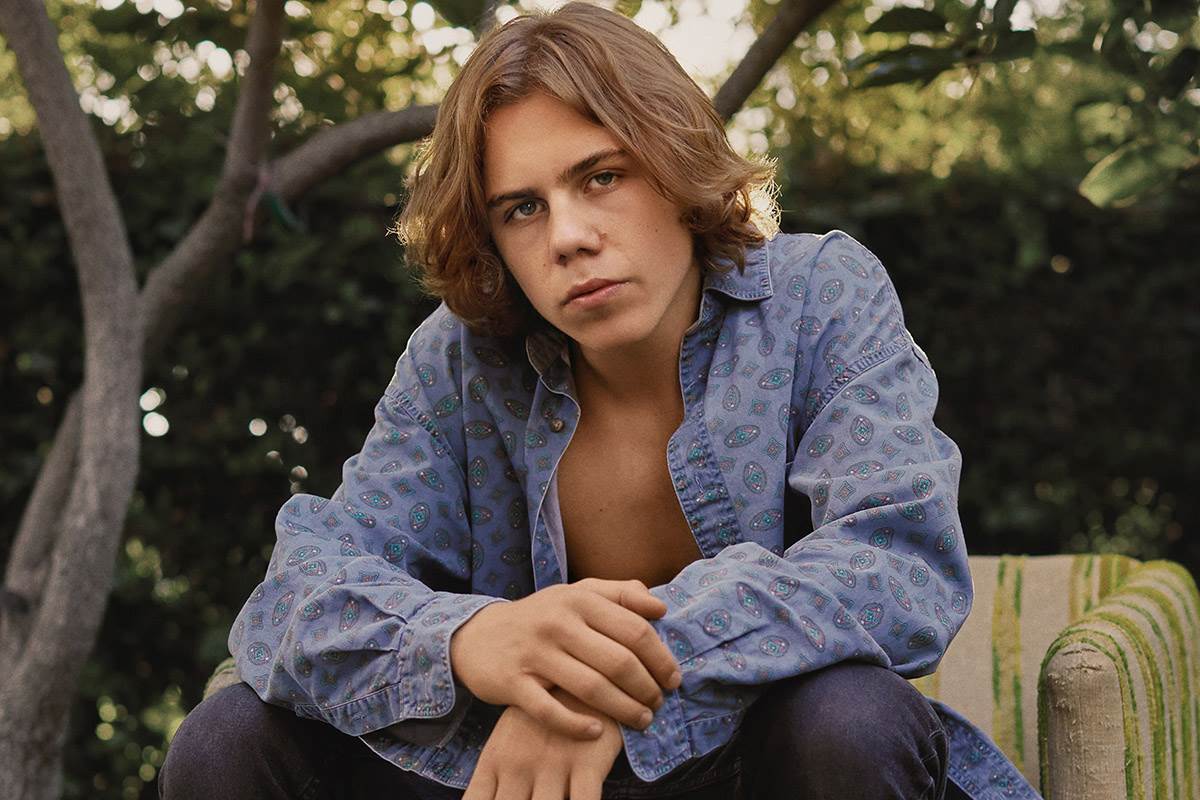

The Kid LAROI

Charlton Kenneth Jeffrey Howard, known as the Kid Laroi, is an Australian singer-songwriter and rapper born on 17 August 2003. He proudly identifies as a Gamilaraay (or Kamilaroi) man, with his ancestry linked to the Stolen Generation. The Kid Laroi gained initial recognition through his connection with American rapper Juice Wrld during a tour in Australia. After partnering with Lil Bibby's Grade A Productions and Columbia Records, he achieved mainstream success in 2021 with the global chart-topping hit "Stay," a collaboration with Justin Bieber. His debut mixtape also soared to number one on both the Australian ARIA Charts and the US Billboard 200, making him the youngest Australian solo artist to accomplish this feat. Notably, "Stay" spent seven non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100, while his song "Without You" and its remix with Miley Cyrus also reached the top ten.

Yothu Yindi

Yothu Yindi is an iconic Australian band known for its unique fusion of contemporary rock music and traditional Indigenous sounds. Formed in 1986 in Yirrkala, Northern Territory, the band's name translates to "child and mother" in the Yolngu Matha language. Led by the visionary Aboriginal musician and activist Mandawuy Yunupingu, Yothu Yindi gained international recognition with their breakthrough hit "Treaty" in 1991, which addressed the need for a treaty with Australia's Indigenous peoples. Combining powerful lyrics with didgeridoo rhythms and other traditional instruments, their music serves as a potent vehicle for advocating Indigenous rights and cultural preservation while also celebrating the richness of Australia's First Nations heritage. Yothu Yindi's legacy continues to resonate, leaving an enduring impact on the music world and Indigenous communities alike.

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu was an extraordinary Australian musician and singer-songwriter renowned for his mesmerising voice and profound musical talent. Born blind on Elcho Island, Northern Territory, in 1971, he belonged to the Gumatj clan of the Yolngu people. Gurrumul learned to play various instruments by ear and became an accomplished guitarist, pianist, and drummer. His music was deeply rooted in the traditions of his Yolngu heritage, often featuring lyrics sung in the Yolngu Matha language. With a captivating blend of folk, rock, and Indigenous influences, Gurrumul's soul-stirring performances transcended cultural barriers, captivating audiences worldwide. His powerful voice conveyed a sense of spirituality and emotion that touched the hearts of listeners and earned him numerous awards and accolades. Tragically, Gurrumul passed away in 2017, leaving behind a profound musical legacy that continues to inspire and enchant audiences globally.

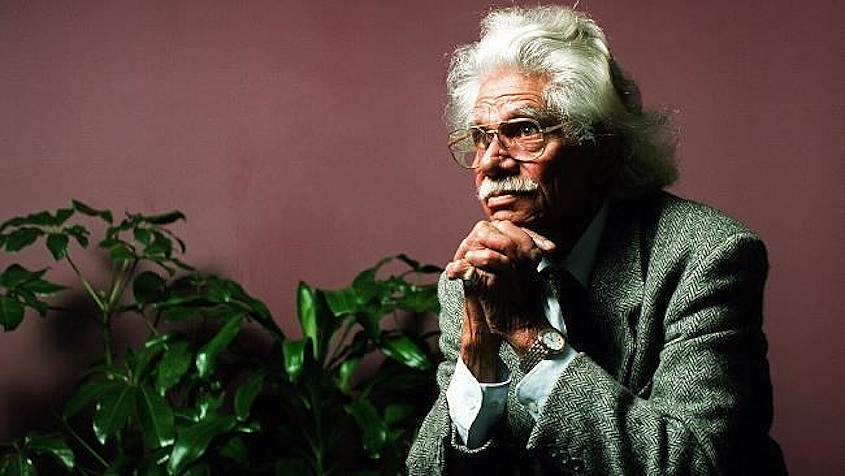

Archie Roach

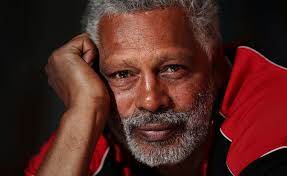

Archie Roach is an influential singer-songwriter whose music reflects the resilience of the human spirit and the profound experiences of his life. Born on January 8, 1956, in Victoria, Australia, he is a proud member of the Stolen Generations, forcibly removed from his family as a child. Despite enduring unimaginable hardships, Roach found solace in music, using it to share his powerful stories and advocate for Indigenous rights and social justice. His soulful folk and roots-inspired melodies, accompanied by heartfelt lyrics, offer a profound insight into the challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Archie Roach's music is a moving tribute to his heritage and a call for understanding and reconciliation. Over several decades, he has become an integral figure in Australian music and an inspiring advocate for cultural preservation and healing.

The Dreaming

The Dreaming refers to an infinite, all-at-once time in which the past, present, and future coexist simultaneously. It is the natural world, especially the land or the country to which a person belongs, which provides the link between the people and The Dreaming.

Dreaming stories carry the truth from the past, together with the code for the lore, which operates in the present. Each story belongs to a long, complex story that establishes the structures of society, rules for social behaviour and the ceremonies performed to ensure the continuity of life and land. Some Dreaming stories discuss consequences and our future.

Stories help explain how the land came to be shaped and inhabited and how to behave and why.

Examples of the art of storytelling can be found at the Dust Echoes website. The Dust Echoes series is a collection of dreamtime stories collected from the Wugularr (Beswick) Community in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. The stories have been screened at film and animation festivals all over the world to great critical acclaim.

Our spirituality is a oneness and an interconnectedness with all that lives and breathes, even with all that does not live or breathe. - Mudrooroo, Aboriginal writer.

Tom Lewis, Actor, Musician, Consultant.

'Dust Echoes is one way that we are bringing everyone back to the same campfire - black and white. We are telling our stories to you in a way you can understand, to help you see, hear and know. And we are telling these stories to ourselves, so that we will always remember, with pride, who we are.'

Spirituality of Land and Sea

Land and the sea are fundamental to the wellbeing of First Nations people. The land is the core of all spirituality. This relationship and the spirit of 'country' are central to the issues that are important to First Nations people today. First Nations people take responsibility and care of the land:

-

Land is 'home'

-

Land is mother

-

Land is steeped in culture

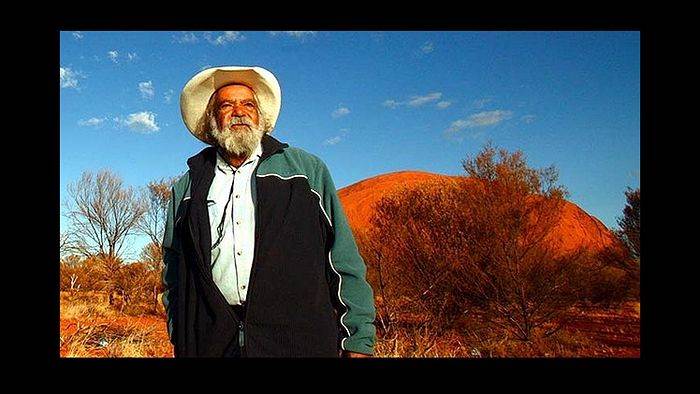

'The Land Owns Us'

According to Bob Randall, a Yankunytjatjara elder and Traditional Owner of Uluru, the concept of "The land owns us" centres on the profound interconnectedness between all living beings. This ancient way of living acknowledges that every living thing is part of a vast family, where humans, animals, plants, and the land are deeply intertwined. This sacred relationship impels us to take on the responsibility of caring for this family with unwavering love and a sense of duty. It calls upon us to cherish and protect the land with unconditional care, recognising that our well-being is inseparable from the well-being of the entire natural world. This traditional wisdom encourages us to live in harmony with nature, fostering a profound respect for the earth and all its inhabitants.

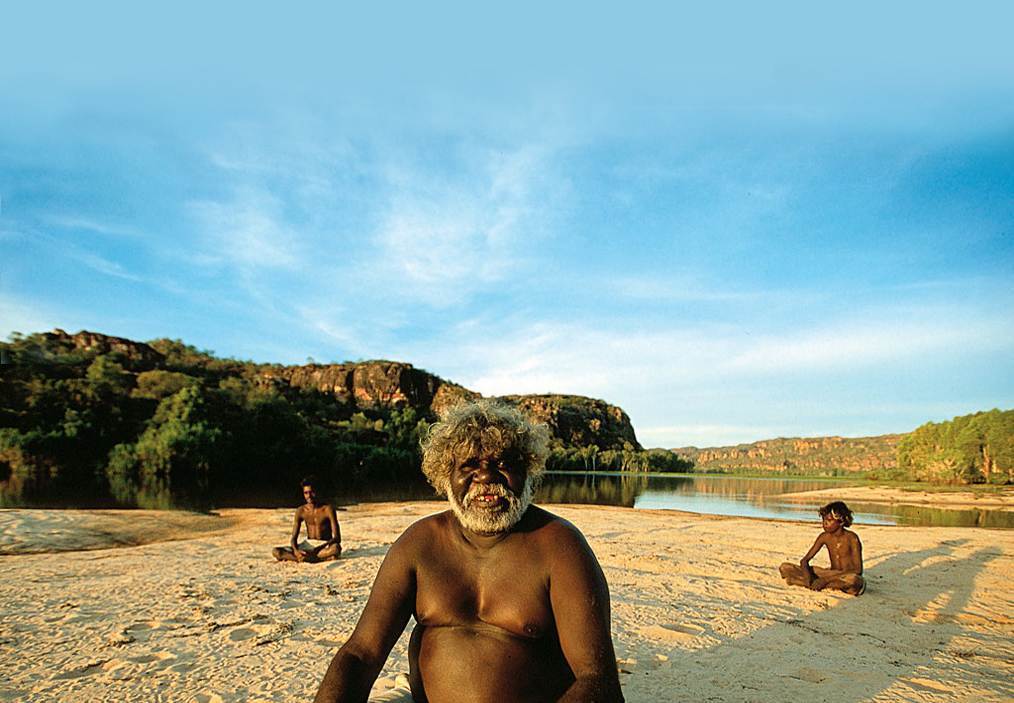

'When you dig 'em hole in that country, you're killing me,' Jeffrey Lee told reporters. 'Money don't mean nothing to me. Country is very important to me.'

To Jeffrey Lee, a senior custodian of the land known as Koonwarra, "Money don't mean nothing to me." Despite having the opportunity to become a millionaire through mining royalties, he chose a different path.

Jeffrey recognised the immense value of his country and its significance to his identity and culture. Instead of allowing an energy company to extract uranium from the land, he made a heartfelt decision. Jeffrey approached the federal government and proposed incorporating the land into Kakadu National Park, thus preserving the land and its cultural importance for future generations. As a ranger in the park, he welcomes visitors and employment opportunities for Aboriginal people. For Jeffrey, the connection to his country outweighed any material wealth, and he remains committed to protecting it for the benefit of all Australians.

Island Custom

For the Torres Strait Islander people, the bond between the land, sea, and Island Custom is not only profound but also integral to their way of life. This ancient connection forms the very foundation of their culture, traditions, and identity in the Torres Strait region. Throughout history, Island Custom has played a pivotal role in shaping the social, political, and economic structures within individual communities.

Island Custom is the traditional guiding force that governs various aspects of life

It provides a framework for interpersonal relationships, community governance, and the distribution of resources. Each community's unique Island Custom reflects their deep understanding of the land and sea and how they intertwine to sustain livelihoods. This harmonious coexistence with nature is central to belief systems, instilling a profound sense of respect and responsibility for the environment. Traditional practices and ceremonies honour the spirits of the land and sea, seeking guidance and protection for their communities.

The Torres Strait Islander people hold steadfastly to their Island Custom

It is a source of cultural strength and unity passed down through generations. The deep connection to the land and sea fosters a strong sense of belonging, reinforcing their identity as custodians of these cherished landscapes. Island Custom is a guiding compass, helping them navigate modern challenges while preserving their cultural heritage and embracing growth opportunities. It remains the heart of their existence, a reminder of their enduring heritage and vital role as guardians of ancestral territories, ensuring the continuity of a thriving way of life across generations.

'The Coming of the Light'

The Coming of the Light festival marks the day the London Missionary Society first arrived in Torres Strait. The missionaries landed at Erub Island on 1 July 1871, introducing Christianity to the region. There were many disadvantages of missionary influences, such as the destruction of traditional cultural religious practices. But there were also positive consequences. Christianity provided a shared identity with the focus on unity that was reinforced through inter-island church meetings, festivals and church openings.

Today, for many Torres Strait Islanders, 'The Coming of the Light' is commemorated on the first of July each year and is regarded as National Torres Strait Islander Day.

The Importance of Elders

The invaluable wisdom of Elders is sought after and cherished, making their counsel and guidance an essential part of community life.

In addition to preserving cultural traditions, Elders act as bridges between past, present, and future, helping to foster a sense of belonging and cultural identity for younger generations. They play a vital role in passing down oral histories, teaching ancestral customs, and nurturing a strong sense of community and pride in one's heritage. Their presence provides an anchor amidst the complexities of the modern world, offering an enduring connection to the spiritual and cultural foundations that have shaped First Nations societies for time immemorial.

It is important to recognise that the title of Elder is not solely determined by age; it is a designation earned through experience, knowledge, and significant contributions to the community. As such, while some individuals may refer to themselves as Elders based on age, traditional First Nations culture upholds a more nuanced and profound understanding of this esteemed role.

Elders' cultural guardianship impacts First Nations cultures nationally and globally.

They sustain unique heritage, promoting awareness and appreciation of diverse traditions. Honouring their wisdom upholds the ancestral legacy and fosters a future celebrating strength and unity. Their teachings guide us toward an inclusive, harmonious world, valuing the profound connection between land, culture, and people.

Culture Exercises

This short quiz reinforces what has been covered so far. For each question, please select the most appropriate definition from the options provided (you can try again if you make an incorrect selection).

Click the Start button when you are ready to load the first question.

Kinship

It is important to understand the concepts of 'family' and 'kinship' for First Nation peoples. The traditional First Nations family structure is significantly different to the Western view of a family unit. Whereas many people live within a nuclear family unit, First Nations people value an extended family system, which often includes distant relatives.

In First Nations communities, society and family are an integral part of a person's life. It is the extended family that teaches how to live, how to treat other people, and how to interact with the land. When working with First Nations people you may find that they rarely call their family members by name. Instead, they use relationship terms such as brother, mother, aunt, or cousin. It is useful to have a general understanding of the Classification System of Kinship.

This 'kinship' system establishes how all community members are related and their position.

Sorry Business Scenario:

Betty is the Manager of a busy team in the State office.

John, a work colleague, asks Betty for a week's leave to attend to 'sorry business'. John explains that his Mother's Uncle has passed away and that he needs to return to his land to attend the funeral.

Sorry business can take some time and supervisors should be sensitive and consider the request for leave for bereavement purposes favourably. Sometimes, this may require flexible working conditions or leave without pay options.

First Nations Languages

How many First Nations languages are spoken today?

In 1788, there were about 250 languages spoken in Australia, plus dialects. Today, only two-thirds of these languages survive and only 20 of them (eight per cent of the original 250) are still strong enough to have a chance of surviving well into the next century.

The languages with the most speakers currently are Arrernte, Djambarrpuyngu/Dhuwal, Pitjantjatjara and Warlpiri. There are also many speakers of Torres Strait Creole and Kriol.

Many languages are no longer spoken in their entirety by anyone; rather, words and phrases are used. There is widespread community support to promote the revival and maintenance of First Nations languages. Bilingual education was introduced in some First Nations communities in the early 1970s and continues today.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flags

Most Australians can identify the flags of the Aboriginal and Torres Strat Islanders. Click on each of the flags now, to learn a little more about their history.

The Aboriginal flag was designed by a central Australian Luritja man, Harold Thomas, to signify the unity of the Aboriginal people during the land rights movement in the 1970s. Divided into two halves, the red base of the flag represents the earth, ochre and the spiritual relationship to the land, while the black panel symbolises the Aboriginal people. The two halves of the flag are connected by a central yellow circle, representing the sun - the constant giver of life.

First flown at Victoria Square in Adelaide on National Aborigines day, July 12, 1971, the flag was proclaimed the official 'Aboriginal flag of Australia' in 1975. In 1995, it was legally recognised by the Australian government as a 'Flag of Australia' under section 5 of the Flags Act 1953.

The Aboriginal Flag

The Torres Strait Islander flag consists of a blue horizontal mid panel, flanked by two green panels. These are separated by thin black lines representing the people. A 5-pointed white star, symbolic of peace and the Aboriginal islander groupings, sits central to the flag. This is surrounded by a 'deri'/'dharri' headdress, symbolic of the Torres Strait Islander people.

The Torres Strait Islander flag was designed by the late Bernard Namok of Thursday Island in 1992. The Torres Strait Islander flag was officially recognised by the Australian Government as an Australian flag in 1995.

The Torres Strait Islander Flag

Welcome to Country

Welcome to Country ceremonies acknowledge the traditional custodians of a particular area or region, demonstrating respect for the First Nations people, culture, and heritage.

Delivered by a Traditional Owner of the land, Welcome to Country symbolises the consent of the traditional landowners for the event to take place on their land by welcoming the event and people in attendance to their country and giving safe passage.

You will have noticed that a Welcome to Country is now typically performed in many varied situations including major sporting events, business gatherings, expos, concerts, etc.

Acknowledgement of Country

You have been asked to perform an Acknowledgement of Country at your next team meeting. Don’t Panic!!!

An Acknowledgement of Country demonstrates respect for the First Nations culture and the Traditional Custodians of the land and acknowledges their continuing relationship and connection with the land and water.

Generally, Acknowledgement of Country takes place at the beginning of a meeting and is undertaken by the chair or speaker. To view guidelines for conducting a Welcome to Country or Acknowledgment of Country, click here.

Scenario

Alan is a Koori man who is always happy to talk about his culture and family with the other team members. He has often mentioned upcoming events such as National Reconciliation Week and NAIDOC Week during team meetings and has requested that we start all formal team meetings with an Acknowledgement of Country.

As the manager, you agree to Alan's request but then, after the team meeting, another team member approaches you to express that she feels it is inappropriate for Alan to “force” cultural matters on everyone and requests that the Acknowledgment of Country not be conducted.

Click the Start button when you are ready to load the first question.

How Might you React to First Nations People Who:

It's essential to remember that each culture has its unique set of nonverbal communication norms, and what may seem harmless or common in one culture might carry different meanings and implications in another. How might you react to First Nations people who, for example:

- don't look you in the eye when you are speaking to them?

- are not answering your questions?

Click on the panels below to overview some key communication cues.

In many First Nations communities, reproduction of the names and photographs of deceased people is restricted during a period of mourning. If there is a need to refer to the deceased person, it is possible to modify their name or use an indirect reference, for example, 'The old man that painted'.

Name Avoidance

In various cultures, direct eye contact may be perceived as impolite or disrespectful. If a First Nations person avoids eye contact, it does not necessarily indicate rudeness. Understanding and respecting diverse cultural norms around eye contact is essential to foster positive communication and cross-cultural understanding.

Eye Contact

Long periods of silence and thought are common. While extended periods of silence might be seen as awkward in some cultures, they are considered natural and reflective to First Nations people. First Nations people listen to others before expressing their views. They may not immediately express their opinion, even if they hold one, demonstrating patience, consideration, and respect for the other person's words. Given time and trust, they will offer their opinions.

Being comfortable in these situations fosters a positive environment for everyone involved.

Silence and Pauses

For First Nations people and many other cultural groups, pointing at someone can be perceived as invasive, disrespectful, and violating personal boundaries. Instead of pointing directly at individuals, consider using open hand gestures or gestures that include the entire group or surroundings. For instance, using an open palm to indicate a general direction or object can be more respectful and inclusive. To avoid misunderstandings, it's best to use more universally understood hand gestures or simply be cautious with gestures that might have diverse interpretations.

Pointing

While there is no single approach that applies to all First Nations people, many individuals may have personal space boundaries. Be observant and sensitive to the cues given by the person you are interacting with. Pay attention to their body language and any signals indicating their preference. If unsure, it's best to err on respecting personal boundaries and allowing for a comfortable distance during the conversation. The key is to treat each person as a unique individual rather than making assumptions based on their cultural background. Respecting personal space demonstrates consideration and cultural sensitivity, fostering positive and meaningful interactions with First Nations people and others from diverse backgrounds.

Personal Space

In some cultures, maintaining a calm and soft-spoken demeanour is valued as a sign of respect and consideration. A gentle tone may also be more appropriate in certain settings, especially when discussing sensitive topics or engaging in meaningful conversations. On the other hand, some First Nations communities may have a more expressive and animated communication style, where vocal inflections and emotional emphasis are common. Such expressive tones may indicate engagement, passion, or warmth in the conversation.

Be prepared to adjust your tone to match the tone of First Nations people you communicate with and be mindful of cultural nuances.

Tone of Voice

Asking Indirect Questions

In First Nations cultures, the art of gathering information relies on a nuanced approach to asking questions. Instead of employing direct and straightforward questions that may be seen as abrupt or intrusive, indirect questioning offers a way of seeking information respectfully while nurturing open communication.

Indirect questioning involves providing information, making statements or observations, and prompting a response in a relaxed environment that promotes a comfortable exchange of ideas. You can often observe the response without putting the other person on the spot, or you can more openly seek their feedback or opinion.

By offering relevant details and context, you create an environment where the other person can comfortably respond with their experiences and reflections.

For instance, let's consider an inquiry about workstation comfort…

- Direct question: "Ella, are you comfortable at your workstation?"

- Indirect question: "A few people seem concerned about their workstation setup; maybe we need to rework the design?"

The indirect question presents a pathway that invites open dialogue without feeling pressured or obligated to respond in a particular way. This subtle and respectful style of questioning emphasises the value of thoughtful communication, fostering a sense of community and collaboration. Click here for more reflection.

Indirect questions foster a collaborative and open atmosphere where individuals feel comfortable expressing their opinions.

Select the preferred approach for seeking input from your colleagues in a workplace situation:

Scenario:

At the weekly team meeting, Judy notices that Peter, a new member of her team who is First Nations, isn't contributing to the group discussion. She wants to find ways to involve Peter in the discussion and help him to feel comfortable participating. What could Judy do?

Feedback

Demonstrating genuine interest in Peter's perspective and needs will foster a supportive environment for him to voice his thoughts.

Judy should set up a private conversation with Peter to discuss anything that she or the team can do to make him feel more comfortable participating in team meetings. Judy should also consider diversity initiatives to help the team gain a better understanding of the various cultures, communication styles, and unique perspectives of the people in the team. By promoting cultural awareness and sensitivity, Judy can ensure that her team creates a more inclusive and respectful workspace where every team member feels valued and empowered to contribute their ideas.

Click here to access a range of ideas to support Judy in such a situation.

History Explains The Current Situation of First Nations Peoples.

This historical overview provides a glimpse into the complex history that shapes the present situation of First Nations peoples in Australia. Understanding this history is crucial to fostering awareness, empathy, and meaningful reconciliation efforts.

The historical overview begins with the discovery of the Torres Strait Islands in 1606 by Spaniard Luis Vaez de Torres, although prior exploration by Chinese, Malay, and Indonesian traders is likely. The 1860s brought an influx of people to the Islands due to the discovery of pearl shell, with settlement primarily on Thursday Island.

The British colonisation of mainland Australia commenced in 1788 with the arrival of the First Fleet in Botany Bay.

Initially, First Nations people assisted British settlers. However, conflicts arose, leading to a belief among settlers that First Nations people were "uncivilised and inferior."

Australia was declared "terra nullius" - or uninhabited.

Upon Federation in 1900, the original Constitution Act excluded Aboriginal people from being considered citizens.

Nevertheless, First Nations men served as soldiers in various wars. In 1967, a significant referendum changed the Australian Constitution, allowing the Commonwealth Government to make specific laws for First Nations people, and including them in the national census.

However, for some First Nations people, the bicentennial celebrations of 1988 were a time of mourning.

What was the 1967 Referendum About?

The 1967 referendum aimed to amend the Constitution to count Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in the national census and give the Commonwealth Government the power to make laws for First Nations people. Over 90% of eligible Australians voted YES, marking a milestone in the reconciliation movement and formal recognition of First Nations peoples as citizens of their own country.

The Stolen Generations

The historical overview sets the stage for understanding the deeply impactful and troubling chapter in Australian history known as the Stolen Generations. The policies and attitudes that evolved during British colonisation, including the perception of First Nations people as "uncivilised and inferior," led to discriminatory practices and forced removals of children from their families and communities.

The stolen generations were placed in church missions or with non-First Nations families, mainly between 1869 and 1969, although in some places children were still being taken as recently as the 1970s.

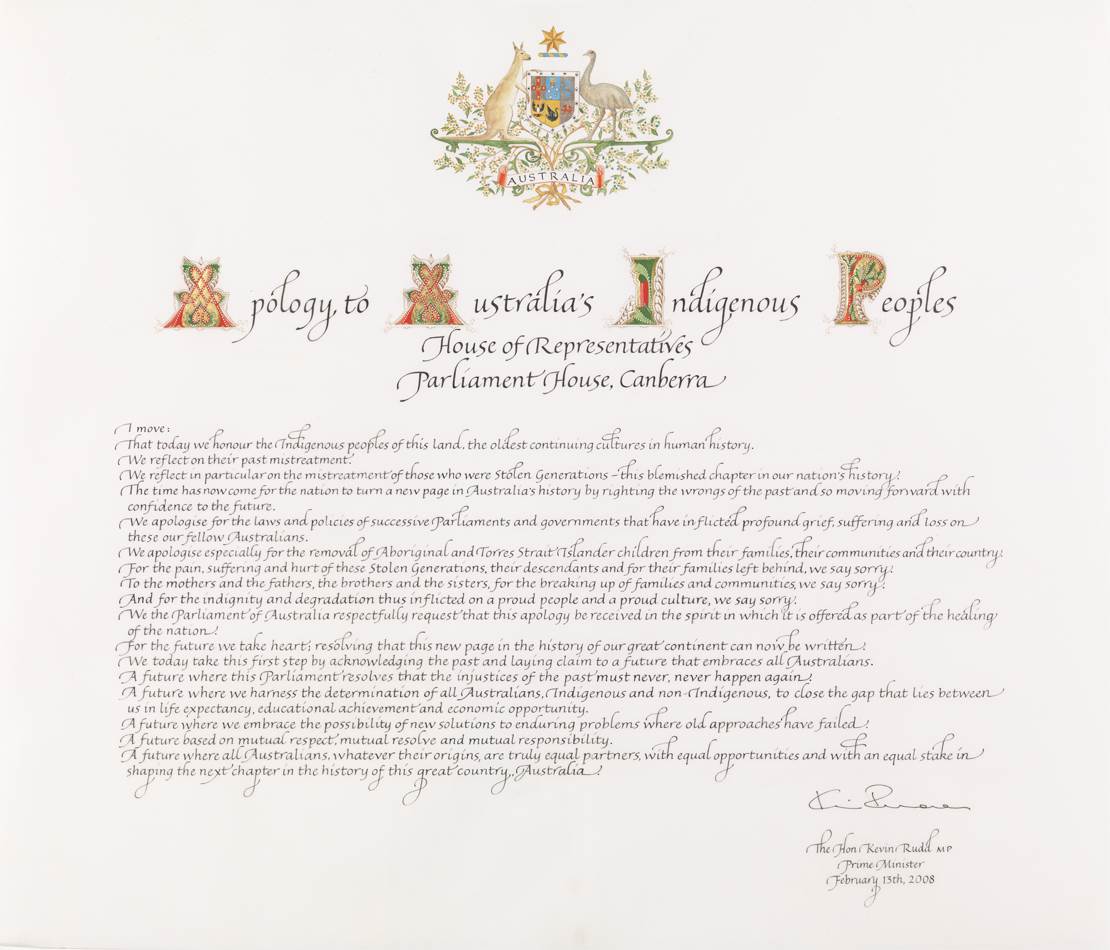

On 13th February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd presented an apology to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community for the Stolen Generation. The apology was seen as a 'first step by acknowledging the past and laying claim to a future that embraces all Australians'.

Click here to access the full text of the apology.

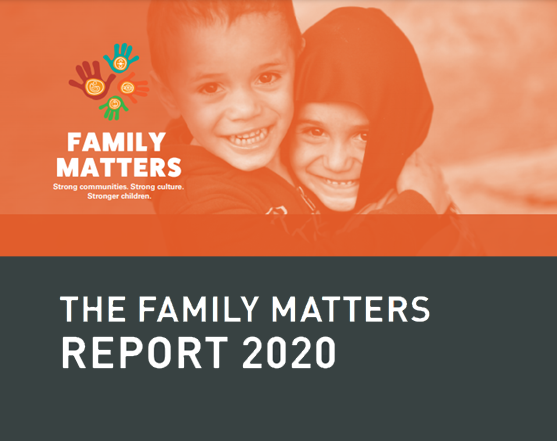

Family Matters Report 2020

This report from 2020 underlines that the struggle continues: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children make up 37% of the total out-of-home care population yet represent only 6% of the total child population in Australia. The rising tide of over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children removed from their families continues at an alarming rate, with most permanently separated from their parents.

"Our children are 9.7 times more likely to be living away from their families than non-Indigenous children, an over-representation that has increased consistently over the last 10 years. It is time to completely change this broken system that is not working for our kids.” Sue-Anne Hunter, Family Matters Chair.

Click here to visit the site

Timeline of Significant Events

Click each of the Year tabs on this dialogue box to overview some of the significant events relating to reconciliation.

1962

The Commonwealth Electoral Act is amended to give the vote to all Aboriginal people.

1967

The Commonwealth Referendum passes. This ends constitutional discrimination, and all Aboriginal people are now counted in the national census.

1971

The first census to include First Nations people.

1972

The Whitlam Government introduces a policy of self-determination. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs was established. The “Aboriginal Embassy' is pitched outside Parliament House in Canberra. The Whitlam Government freezes all applications for mining and exploration on Commonwealth Aboriginal Reserves.

1976

Federal Parliament passes the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act.

1987

A Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody begins.

1991

The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation Act passes through Federal Parliament. The Council is formed. The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody presents its Report and Recommendations to the Federal Parliament.

1992

The High Court of Australia rules in the Mabo case that native title exists over particular kinds of land and that Australia never was terra nullius or 'empty land'.

1993

The Federal Government establishes the Office of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner in response to issues of discrimination and disadvantage highlighted by the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission's National Inquiry into Racist Violence.

1995

The National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families is established in response to efforts made by key agencies and communities.

1996

The Wik Decision. The High Court found that pastoral leases did not necessarily extinguish native title (as earlier ruled) and that both could co-exist but where there was conflict, native title rights were subordinate to the rights of the pastoral leaseholder.

1997

The 700-page report of the 'Stolen Children' Nation Inquiry 'Bringing Them Home' was tabled in Federal Parliament.

2000

National Recognition Week and People's Walk for Reconciliation.

2004

Abolition of ATSIC.

Formation of National Indigenous Council.

2008

The apology in the Australian Federal Parliament on 13 February 2008 to the Stolen Generations of Australia became a defining moment in the nation's history.

2017

On the 26 May 2017 during the National Constitutional Convention, 250 First Nations Delegates’ from across Australia came together to agree that in Australia sovereignty has never been ceded or extinguished. From this agreement, “the Uluru Statement from the Heart” was formed.

2022

In May 2022, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese made a commitment to establish a Voice to Parliament - a permanent body representing First Nations people that would advise government on policies and laws which impact their lives.

2023

In late 2023, the Australian Government agreed to have a referendum to let Australians decide whether to establish the Voice in the Constitution.

Australians went to the polls 14th October 2023 in a historic referendum - that determined if First Nations people should be recognised in the country’s constitution through a voice to parliament. The question that was put to voters is whether to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Waterhole - Uluru Statement from the Heart

Put simply, the Uluru Statement from the Heart is an invitation from First Nations Peoples to consider legal and structural reforms to redesign the relationship between First Nations Peoples and the Australian population. The Statement calls for two changes:

-

Voice to Parliament, which needs to be enshrined in the Constitution of Australia to ensure it remains a permanent part of our democracy.

-

Makarrata Commission to supervise agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

Why do we need to change the Constitution?

The vote was the most significant step in a decades-long push for constitutional recognition of Australia’s Indigenous people. It was the culmination of a six-year-long process since the ULURU Statement from the Heart and was delivered to the Australian people, calling for a constitutionally enshrined Voice, a committee of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to give advice on policies affecting First Nations Australians.

Constitutional enshrinement can only be achieved through a referendum.

This means the constitution cannot be altered without 'the approval of the people'.

All Australians of voting age had the opportunity to vote to enshrine a First Nations Voice into the Australian Constitution.

How would a Voice to Parliament have helped First Nations people?

Many of the concerns First Nations people face are varied and complex. The issues are bound to factors such as cultural differences, remote locations, poverty, English as a second or third language, and failed and racist past government policies.

A Voice would have meant the Government of the day would have better quality information about First Nations issues - from First Nations people. First Nations people understand the issues affecting their communities and are best placed to contribute to the solutions.

Resource allocation would have been more accurately targeted.

Better laws would have improved outcomes across all social measurements, including health, housing, criminal justice, and education.

Voice supporters and the Albanese government maintain that such a mechanism would help improve shocking shortfalls in life outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. They said a voice could assist in closing the gap on indicators such as life expectancy, suicide rates, and incarceration.

Although the YES campaign sought to paint the referendum as a unifying and positive moment for the country, 60% of Australians voted No.

Let’s take a moment to reinforce some key points.

Click the Next button when you are ready to load the first question in our knowledge check.

What is the Cause of the First Nations Health Equality Gap?

The First Nations health equality gap stems from a complex array of factors. Historical factors, including colonisation, dispossession, and discrimination, have led to intergenerational impacts on health and well-being. Socioeconomic determinants such as lower education levels, higher unemployment rates, inadequate housing, and limited access to resources contribute to disparities. Cultural factors like language barriers, cultural differences in healthcare practices, and a lack of culturally appropriate services also play a role. Furthermore, systemic issues within the healthcare system, including a lack of accessibility, cultural safety, and appropriate funding, contribute to the gap.

Addressing these multifaceted factors is crucial for achieving health equity and closing the gap for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Overcrowded, poor-quality housing in many communities, limited access to healthy food, and the absence of access to Primary Health Care are major contributors to illnesses that should be preventable and that tend to become chronic problems.

Cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, diabetes, musculoskeletal conditions, kidney disease, and eye and ear problems are massive challenges for First Nations people.

For First Nations people, good health is more than the absence of disease or illness; it is a holistic concept that includes physical, social, emotional, cultural, and spiritual wellbeing, for both the individual and the community.

Closing the Gap

The objective of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) is to enable First Nations people and governments to work together to overcome the inequality experienced by First Nations people and achieve life outcomes equal to all Australians.

Key targets of the Closing the Gap Agreement are Listed Below:

- Everyone enjoys long and healthy lives

- Children are born healthy and strong

- Children are engaged in high-quality, culturally appropriate early childhood education in their early years

- Children thrive in their early years

- Students achieve their full potential

- Students reach their full potential through further education pathways

- Youth are engaged in employment or education

- Strong economic participation and development of people and their communities

- People can secure appropriate, affordable housing that is aligned with their priorities and need

- Adults are not overrepresented in the criminal justice system

- Young people are not overrepresented in the criminal justice system

- Children are not overrepresented in the child protection system

- Families and households are safe

- People enjoy high levels of social and emotional wellbeing

- People maintain a distinctive cultural, spiritual, physical, and economic relationship with their land and waters

- Cultures and languages are strong, supported, and flourishing

- People have access to information and services enabling participation in informed decision-making regarding their own lives.

Click here for further information

First Nations People Experience Much Higher Levels of Unemployment.

There is a clear link between unemployment and other aspects of disadvantage. Unemployment is linked to:

-

poor health

-

poor living standards

-

low self-esteem

-

imprisonment and substance misuse

Being employed leads to improved wealth and asset creation for families and communities, which in turn has a positive influence on the health and education of children. Finding ways to increase the economic participation of the First Nations working-age population is important for supporting Government initiatives.

Factors that can make it difficult for First Nations people to obtain work include:

-

lack of relevant training

-

lack of exposure to the mainstream workforce

-

the culture of work organisations and the expectations of organisations

-

the challenges involved in balancing family and community obligations with the demands of full-time work

-

poor health

Barriers often stem from cultural differences and a lack of knowledge of recruitment processes by First Nations job seekers. These can result in under-prepared work resumes, inappropriately addressing key selection criteria or a lower level of interest from candidates if there are no other First Nations people working in the organisation. Many of the barriers faced by First Nations people can be understood and overcome through useful strategies for recruiting and retaining employees.

Celebrating First Nations Culture Waterhole

There have been many successful and influential First Nations people involved in various fields such as sport, arts, politics, media and lore. David Unaipon (1872 - 1967) was a Ngarrindjeri man, inventor and writer. He based his helicopter design on the principal of a boomerang. David Unaipon's portrait is depicted on the Australian $50 note, along with drawings from one of his inventions and an extract from his original manuscript, Legendary Tales of Australian Aborigines.

Prominent First Nations People

We would now like to introduce you to the many First Nations people who have been awarded Australian of the Year or Young Australian of the Year. First Nations people should know that this will contain images, voices, and names of deceased persons.

2020 - Ash Barty

Ash Barty, a tennis sensation and proud Ngarigo woman, has risen to global prominence with her exceptional skills and inspiring journey. As the world's No. 1 singles player and a Grand Slam champion, she stands as a role model for athletes and Indigenous Australians alike. Barty's commitment to her roots and cultural representation adds to her remarkable legacy, making her an admired figure worldwide. Her sportsmanship, humility, and dedication to her community solidify her as an enduring icon in Australian sports history, inspiring future generations with her remarkable achievements and impact on the world of tennis.

2019 - Danzal Baker (Baker Boy)

Danzal Baker, widely known by his stage name "Baker Boy," is a remarkable talent in the world of music. Hailing from the Arnhem Land region in the Northern Territory of Australia, Baker Boy has made a significant impact on the music scene with his unique blend of hip-hop and traditional Indigenous sounds. His powerful performances and infectious energy have earned him accolades and recognition, solidifying his position as a prominent figure in the Australian music industry. Beyond his musical achievements, Baker Boy takes great pride in his Indigenous heritage and uses his platform to promote and celebrate his Yolngu culture, making him an inspiring role model for both the music industry and his community.

2014 - Adam Goodes

Adam Goodes, an iconic figure in Australian sports and Indigenous advocacy, has left an indelible mark on and off the field. With a celebrated AFL career playing for the Sydney Swans, Goodes achieved numerous accolades, including two Brownlow Medals and four All-Australian selections. Beyond his athletic prowess, he is revered for his tireless efforts in championing Indigenous rights and promoting cultural awareness. As an Adnyamathanha and Narungga man, Goodes has fearlessly confronted issues of racism and inequality, using his platform to drive positive change and inspire conversations about reconciliation and social justice. Adam Goodes' legacy extends far beyond his sporting achievements, as he continues to stand as a powerful voice for his community and the wider Australian society.

2009 - Mick Dodson

Mick Dodson, a prominent figure in the realm of Indigenous affairs and human rights, has made a significant impact on the Australian landscape. As a highly respected Yawuru man from the Broome region in Western Australia, Dodson has been a leading advocate for Indigenous rights, reconciliation, and social justice. Throughout his career, he has held key roles in various organizations and committees, contributing to policy development and promoting positive change for First Nations peoples. Dodson's unwavering commitment to bridging the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians has earned him widespread recognition, and his dedication to building a more equitable and inclusive society continues to inspire and influence meaningful change across the nation.

2007 - Tania Major

Tania Major, an inspiring and influential figure, has played a significant role in advocating for Indigenous rights and social justice in Australia. Hailing from the Torres Strait Islands, Major has been a dedicated and passionate advocate for her community and Indigenous peoples across the nation. Throughout her career, she has worked tirelessly to address issues such as health, education, and economic empowerment, aiming to create positive change and opportunities for First Nations people. As a respected leader and public speaker, Major has used her platform to raise awareness about the challenges faced by Indigenous communities and promote cultural preservation and recognition. Her impactful contributions continue to resonate, leaving a legacy of empowerment and unity for First Nations peoples.

1998 - Cathy Freeman

Cathy Freeman, an Olympic gold medalist and world champion athlete, has left an indelible mark on Australian sports and Indigenous representation. At the 2000 Sydney Olympics, Cathy became the first Aboriginal Australian to win an individual Olympic gold medal. Freeman has been a passionate advocate for Indigenous rights and reconciliation. Proud of her Indigenous heritage as a member of the Ku-Ku Yalanji people, she has used her platform to raise awareness about the challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Through her Cathy Freeman Foundation, she has worked tirelessly to improve educational opportunities for Indigenous children and empower them to reach their full potential. She continues to inspire generations of Australians and Indigenous youth, demonstrating the transformative power of dedication, resilience, and leadership.

1997 - Nova Peris

A proud member of the Yawuru people, Nova Peris has left an enduring impact on Australian sports and politics. She made history at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics as the first Indigenous Australian to win an Olympic gold medal (in Australia's women's hockey team). Transitioning to politics, she became the first Aboriginal woman to be elected to the Australian Parliament in 2013. Nova Peris has tirelessly advocated for Indigenous rights, health, and education, using her platform to raise awareness about the challenges faced by her community. Her achievements and commitment to empowerment have made her a respected and inspiring figure for First Nations Australians and the nation as a whole.

1992 - Mandawuy Yunupingu

Mandawuy Yunupingu, a visionary First Nations Australian, made a profound impact as the lead singer of Yothu Yindi, transcending borders and advocating for First Nations rights and reconciliation through his powerful music. A proud Yolngu man and a respected leader, he became a symbol of resilience and wisdom for First Nations communities. Yunupingu's enduring legacy continues to inspire artists and activists, emphasising the importance of preserving culture and language, land rights, and fostering understanding among all Australians. His contributions shape Australia's cultural landscape, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's history. Mandawuy Yunupingu passed on June 2, 2013.

1984 - Lowitja O'Donoghue

As a proud Yankunytjatjara and Arrernte woman, Lowitja O'Donoghue has been a champion for the rights and recognition of First Nations peoples. Throughout her career, O'Donoghue has held various leadership roles, including serving as the Chairperson of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). Her tireless efforts in promoting reconciliation, cultural preservation, and social justice have earned her widespread respect and admiration. As a passionate advocate, she has used her platform to address issues such as healthcare, education, and land rights, leaving a lasting legacy of empowerment and progress for First Nations communities.

1982 - Mark Ella

Mark Ella, the iconic Australian rugby union player, left an indelible mark during the 1980s with his exceptional talents and vision on the rugby field. As a gifted fly-half, he played a pivotal role in the success of the Australian national team and the New South Wales Waratahs, leading Australia to a memorable series victory over the All Blacks in 1980. Beyond his athletic achievements, Ella's sportsmanship and dedication to the game continue to inspire aspiring rugby players. His legacy endures, as he remains involved in rugby through coaching and mentoring, making him a revered and enduring figure in the world of Australian rugby.

1979 - Neville Bonner

Neville Bonner, a trailblazer in Australian politics, made history as the first Aboriginal Australian to serve in the Federal Parliament. Born in 1922, he overcame significant challenges to become a respected leader and advocate for Indigenous rights and reconciliation. Bonner's political career began in 1971 when he was appointed to fill a Senate vacancy, paving the way for his historic election as a Senator in his own right later that year. Throughout his time in Parliament, he championed issues of importance to First Nations peoples, including land rights and social justice. His dedication to promoting understanding and unity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians earned him widespread admiration and respect. Neville Bonner's legacy as a visionary leader inspires the nation, reminding us of the enduring impact one person can have in shaping a more inclusive and equitable society.

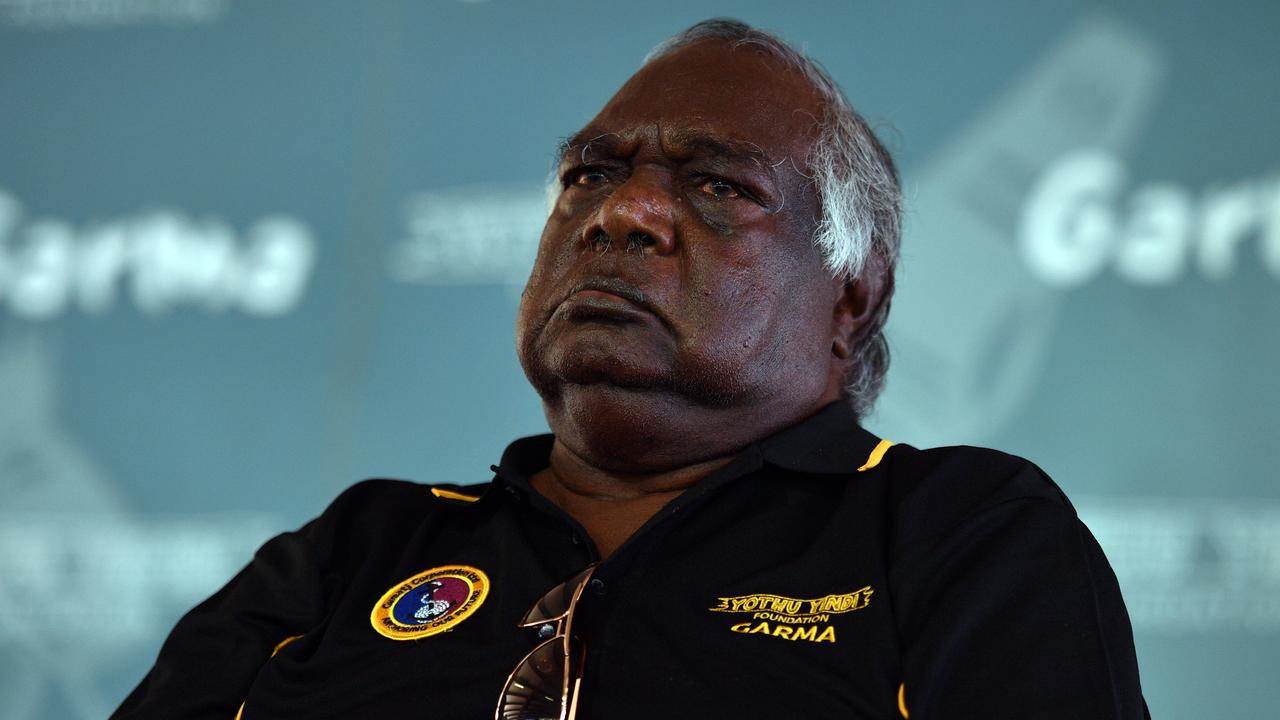

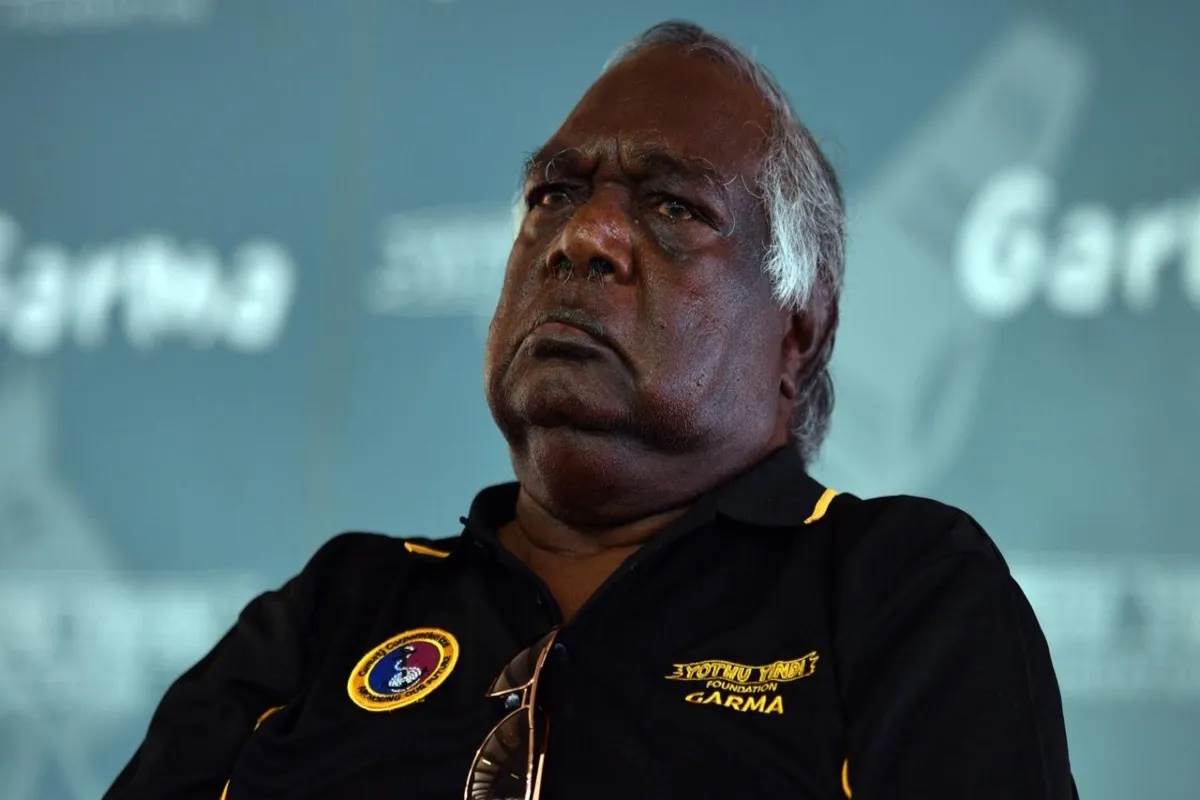

1978 - Galarrwuy Yunupingu

Galarrwuy Yunupingu, a highly respected Yolngu elder and visionary leader, has been a tireless advocate for Indigenous rights and cultural preservation in Australia. Hailing from the Gumatj clan in Arnhem Land, he has played a pivotal role in securing land rights and promoting self-determination for First Nations communities. His wisdom and expertise have earned him admiration nationally and internationally, and he remains a revered figure in the journey towards reconciliation and Indigenous empowerment. Beyond his advocacy, Yunupingu's artistic talents as a singer, songwriter, and storyteller have been instrumental in preserving and sharing Yolngu culture, making him a truly influential and inspirational force in Australian society.

1971 - Evonne Goolagong Cawley

Evonne Goolagong Cawley, the trailblazing Australian tennis legend and proud Wiradjuri woman, has left an enduring mark on sports and society. Her graceful playing style and remarkable achievements on the tennis court earned her numerous Grand Slam titles, including Wimbledon and the Australian Open. Beyond her athletic prowess, she has been an inspirational figure and advocate for diversity, serving as a role model for Indigenous Australians and women worldwide. Goolagong Cawley's dedication to promoting tennis and providing opportunities for young Indigenous players has had a transformative impact on the sport's inclusivity. Her remarkable legacy as a symbol of excellence, empowerment, and positive spirit continues to inspire generations of athletes and Australians.

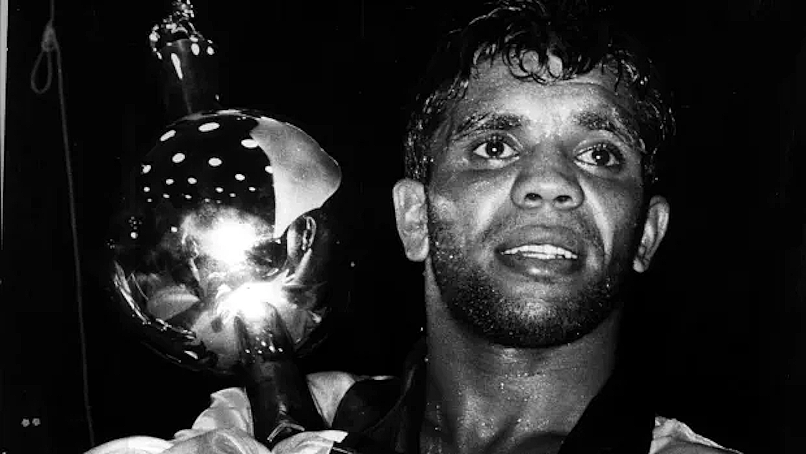

1968 - Lionel Rose

Lionel Rose, a pioneering Australian boxer, holds a revered place in sporting history and Indigenous pride. Born in 1948 and a proud Wurundjeri man, he rose to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s, captivating the nation with his extraordinary boxing skills and determination. In 1968, Rose made history by becoming the first Indigenous Australian to win a world boxing title, securing the bantamweight championship. His remarkable achievement ignited a sense of national pride and paved the way for other Indigenous athletes. Beyond the boxing ring, Rose was a symbol of resilience and inspiration, using his platform to advocate for Indigenous rights and social change. His enduring legacy as a trailblazer and sports icon continues to inspire and uplift communities, leaving an indelible mark on the history of Australian sports and the fight for Indigenous recognition.

Cultural Events

On 13 February 2008 then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd offered an apology to the Stolen Generation. The apology was a crucial step in our reconciliation journey and was a formal acknowledgement of the experiences of the 'Stolen Generations' and the profound sorrow caused by past government practices.

Australia hosts several significant annual cultural events that play a crucial role in supporting and celebrating First Nations people and their rich heritage...

National Reconciliation Week

- the former marks the anniversary of the 1967 referendum in Australia; and

- the latter marks the anniversary of the High Court of Australia's judgement on the Mabo v Queensland case, 1992.

Anniversary of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted by the General Assembly on Thursday, 13 September 2007, marking a historic moment in international human rights as it sets out the individual and collective rights of Indigenous peoples around the world and aims to protect their cultural, social, and economic rights.

Celebrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Culture

NAIDOC stands for the National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee. Its origins can be traced to the emergence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups in the 1920s, which sought to increase awareness in the wider community of the status and treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia each July to celebrate the history, culture and achievements across all fields, including music, art, culture, education, sport, employment and politics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Each year one of Australia's capital cities hosts the National NAIDOC Ball and Awards Ceremony.

The Awards recognise significant contributions by First Nations people. NAIDOC is celebrated not only in First Nations communities but by Australians from all walks of life. The week is a great opportunity to participate in a range of activities and to support your local First Nations communities.

Reconciliation allows us to work together to solve problems and generate success that is in everyone's best interests. It includes:

-

raising awareness and knowledge of First Nations history and culture

-

changing attitudes that are often based on myths and misunderstandings.

-

encouraging action where everyone plays their part in building a better relationship between us as fellow Australians.

Reconciliation Action Plan

A Reconciliation Action Plan specifies actions for encouraging a respectful work culture and building stronger relationships with First Nations peoples in your organisation and in the community. All Australians have a role to play in helping achieve objectives for reconciliation.

Reconciliation Action Plans (RAP) assist businesses to embed the principles and purpose of reconciliation. The RAP network is a diverse group of over 2,400 organisations that directly impact over 3 million Australians at work every day. There are four levels of a RAP; Reflect, Innovate, Stretch and Elevate.

Click here to access a sample vision statement.

Supply Nation is the Australian Leader in Supplier Diversity.

Through Supply Nation, 4,300 (at last count!) verified First Nations businesses are connecting with more than 740 corporate, government, and not-for-profit contacts in every state and territory.

Supply Nation brings together the biggest national database of First Nations businesses with the procurement teams of Australia’s leading organisations to help them engage, create relationships, and do more business.

Credits

The content of this course was collaboratively developed by Interaction Training and the Australian National University, with the support and assistance of the Indigenous Employees Network (IEN) and Reconciliation Ambassador Network (RAN). We also extend our heartfelt gratitude to Wade Krueger and our esteemed First Nations consultation team at KCS, whose invaluable input and ongoing collaboration continue to ensure the relevance of this essential content. Together, we strive to honour and acknowledge the importance of First Nations perspectives and contribute to building a more inclusive and culturally respectful community.

Click here to display image contribution credits.

Disclaimer

This is a generic course, so before we continue, we need you to confirm your understanding that if any policies specific to your workplace conflict with those presented in this course, then you must apply your local workplace policies and procedures rather than those presented here.

Well done

You have now visited and completed all the waterholes. To exit the course and save your work, please be sure to click on the Save and Exit button below.

Copyright 2021: Interaction Training